Totalitarianism in the feed: What communication design can achieve today

Reading Time: 10 minutes

Topics: #motivation, #activism, #political design, #news, #journalism, #remembrance, #history, #fake news, #mobilization, #political action

Introduction

The Year 2016

The following lines are from the preface of my BA thesis, „Motivation+Action“ which I wrote in 2016. In this thesis, I explored the possibilities of graphic design for responding to political issues and informing people. This is achieved—in addition to the textual/theoretical section and an extensive collection of images and quotations that illustrate the motivation—through practical examples of interventions in public spaces. This constitutes the action aspect. The central idea of this thesis was that the most effective lever for a graphic designer lies in visualizing problems, revealing what is hidden, and intervening with this information in people‘s everyday lives.

Foreword to the work „Motivation+Action“ (translated)

“The following pages are intended to be more than just a guide that motivates creatively drawing attention to social problems in one‘s own environment. This publication aims to overcome the powerless attitude towards major social problems with concrete questions and instructions for action. This publication is intended to awaken the reader‘s curiosity to discover their surroundings and to intervene politically in their environment. One should not expect to find a finished, universally applicable project here. Rather, the work represents an inspiration for activism in the public sphere. [...] Michael Schmitz, May 2016”[1]

[2] The first entry from the publication „Motivation+Action“

2016

Three questions from 2016 – three levers for shaping 2026: Visibility, participation, memory.

I would like to begin this post with a moment you probably know: You are scrolling through your feed, and between vacation photos and product videos, a post appears that “just asks a question.” A short sentence, neatly formatted, an image that looks like the truth. You notice: This thing isn‘t loud. It isn‘t even overtly evil. It‘s… plausible. And that‘s precisely what makes it dangerous.

In my 2016 BA thesis, I asked whether design skills could help move people out of a state of powerlessness—toward attention, engagement, and intervention in the public sphere. Ten years later, the situation isn‘t „new,“ but it‘s more complex: ongoing crises, polarization, platform logics, floods of AI content, a palpable yearning for order—and a form of politics that often feels more like PR than democratic negotiation. This is the framework for this essay, a response to Adorno and Horkheimer:

Questions

The three questions

1) Can we use our communication skills to draw attention to the rise of totalitarianism?

2) Can we mobilize people and thereby increase our influence on governments?

3) How can we keep history alive in our consciousness so that we can learn from our mistakes?

Answers

1. Can we use our communication skills to draw attention to the rise of totalitarianism?

Yes – but not simply by raising our voices. From a design perspective, it‘s less about „attention“ than about recognizability. Totalitarian tendencies often manifest today as oversimplification: clear enemy images, seemingly inevitable solutions, a tone of „common sense“ that ridicules complexity. Design can function here like an analytical tool: We can make the mechanics of such messages visible without reproducing them. This begins with translating frames („us against them,“ state of emergency, scapegoat) into comprehensible structures: claim, omission, benefit, target audience. Instead of creating counter-slogans, we can design contextual layers that show what‘s missing: data, historical parallels, interests. Crucially, this involves an ethic of non-reinforcement: no replication of enemy-image aesthetics, no outrage as an end in itself. Good communication design creates subtle friction that interrupts the reflex to share: quick checks, clear sources, and legible uncertainties. In this way, design becomes not a loudspeaker, but a lens that reveals patterns—and thus enables action in the first place.

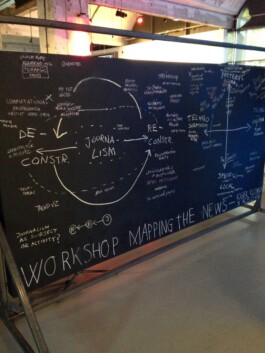

[3] Workshop result in the New Newsroom (2018), Dutch Design Week, Eindhoven, Photo Credits: Michael Schmitz

The New Newsroom (Media Narratives)

The exhibition “The New Newsroom” at MU Hybrid Art House brings together journalists, technologists, artists, and designers to explore innovative formats of news production and to analyze and present news in creative ways. In an interactive newsroom, journalism and design merge, while visitors themselves become part of the news world and can shape headlines.

[4] Logo: Forensic Architecture, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

Forensic Architecture (Visual Investigations)

Forensic Architecture uses cartographic/visual reconstructions, interactive platforms, and published reports to document state violence, repression, and “digital violence”—often in contexts where power relies precisely on opacity. This is communication design as evidence: visualization not for illustration, but as a tool to document authoritarian practices and make them publicly negotiable.

2. Can we mobilize people and thereby increase our influence on governments?

Yes – if we understand mobilization as process design, not as campaign aesthetics. From a designer‘s perspective, many political messages fail not because of a lack of conviction, but because they lack relevance: people know something is wrong, but they don‘t know what concrete steps to take without feeling overwhelmed or ridiculed. Design can bridge this gap by creating chains of action: from initial contact to a small, safe action, all the way to coordinated influence. This requires clear target audiences (who really decides?), a focused demand (one sentence), and micro-commitments (a 30-second entry point instead of a heroic deed). Good mobilization design offers roles: „If you have 10 minutes, do X. If you have 1 hour, do Y.“ It makes processes visible: deadlines, responsibilities, procedures – and translates political processes into understandable interfaces (contact kits, conversation scripts, briefings). Impact is achieved when communication leads to genuine decision-making processes: hearings, consultations, committees, local institutions. Design then not only amplifies opinions but also empowers action – transforming isolated outrage into collective, justifiable pressure.

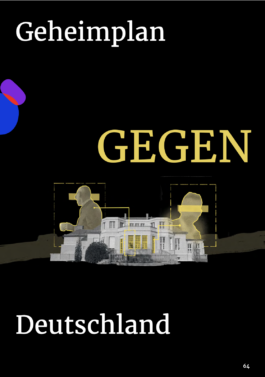

[5] Spreads from: correctiv Jahresbericht 2024, copyright: correctiv, Layout: Michael Schmitz for correctiv

[5] Spreads from: correctiv Jahresbericht 2024, copyright: correctiv, Layout: Michael Schmitz for correctiv

Correctiv (Mass mobilization following journalistic publications)

Correctiv is a public-interest media organization that strengthens democracy. As a multi-award-winning newsroom, we stand for investigative journalism. We spark public debate, collaborate with citizens on our research, and promote society through our educational programs.

[6] Logo "Abgeordnetenwatch", 2026, License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, Author: Parlamentwatch e.V.

abgeordnetenwatch.de (Parliament Watch)

A platform that facilitates public questions and answers between citizens and elected officials, thereby strengthening transparency, accountability, and participation. The communicative key lies in the public nature of the interaction: questions and answers remain visible, comparable, and quotable – thus generating gentle but real pressure on representatives.

3) How can we keep history alive in our consciousness so we can learn from mistakes?

History doesn‘t stay „in our consciousness“ because it‘s important—it stays alive when it takes on a form that recurs. From a designer‘s perspective, memory is an infrastructure: rhythm, places, repetition, connection.

The problem of the present isn‘t ignorance, but rather superimposition: current events consume the past, and without a past, authoritarian patterns appear as new solutions instead of old mistakes.

Design can achieve two things here: First, it can tell history as a mechanism, not as an anniversary. Instead of „back then...“ we show: What steps led to this point? Which terms were shifted? Which exceptions were normalized? Social media can also be used to engage younger people with these topics. Second, memory must remain actionable. Furthermore, design can bring narrative into the „present.“ This includes discussion prompts, local reference points, and concrete opportunities for participation. Site markers (campus/city/institution) are particularly effective, bringing memory from the social media feed into everyday life. In this way, history enters the everyday. Techniques such as VR or geo-caching allow for the creation of particularly interactive formats.

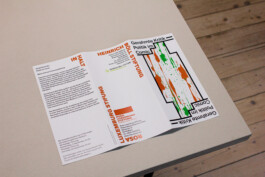

[7] Flyer for the exhibition 2020, Crdits: Own Photography

Gerahmte Kritik – Politics in Comics

(Heinrich Böll Stiftung RLP, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung RLP)

The decentralized exhibition „Gerahmte Kritik – Politics in Comics,“ presented by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Rhineland-Palatinate and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Rhineland-Palatinate, demonstrates how the medium of comics addresses and makes accessible historical and political themes such as colonialism, National Socialism, and social exclusion. By displaying the exhibition in shop windows in Mainz‘s old town and new town, history is made visible in the public sphere – where people encounter it unfiltered in their everyday lives.

[8] View of an exhibition artifact in a shop-window in Mainz, Copyright: Own Photography

Nächstes Jahr In / Next Year in (Heinrich Böll Stiftung RLP, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung RLP)

Jewish life in what is now Germany can be documented for over 1700 years; in Mainz, it is assumed to date back to the 5th century and earlier. Jewish life has always been characterized by exclusion, assimilation, persecution, departure, arrival, and emancipation.

The window display comic exhibition „Next Year In“ presents various aspects of Jewish life in comic form at nine locations in Mainz‘s Neustadt district and is a collaboration between the Heinrich Böll Foundation Rhineland-Palatinate and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Rhineland-Palatinate.

Conclusion

As we saw in the preceding considerations, we can answer the questions from the bachelor‘s thesis as follows:

1) Can we use our communication skills to draw attention to the rise of totalitarianism?

Yes, clear and creative communication—whether through journalism, art, or social media—can make totalitarian tendencies visible and raise awareness among a broad public. Stories that evoke emotions and convey facts in an understandable way often break through indifference. Formats such as graphic novels, documentaries, or interactive exhibitions, which make complex topics tangible, are particularly effective in this regard. Open debate and the exchange about democratic values strengthen the resilience of society. It is important that we create spaces where critical voices are heard and shared.

2) Can we mobilize people and thereby increase our influence on governments?

Mobilization succeeds when we emphasize shared values and demonstrate concrete possibilities for action—from demonstrations and campaigns to artistic actions. Social movements show that collective action can generate political pressure and force change. Platforms like social media enable rapid networking today, but in my experience, sustainable change arises primarily through local initiatives and personal conversations. This is where local action can directly begin.

3) How can we keep history alive in our collective consciousness to learn from mistakes?

History remains present when we anchor it in everyday life—for example, through decentralized exhibitions, school projects, or easily accessible digital archives. Art and culture, such as comics or theater, make historical events tangible and encourage reflection. Commemoration should not be merely ritualistic but must be linked to current debates to establish connections to the present. It is particularly effective when those affected and eyewitnesses themselves have a voice and share their stories. Only in this way does remembrance become an active engagement and not merely a duty.

[9] Commemoration of the 2016 attack at the Olympia Shopping Centre (OEZ) in Munich,

copyright: Thomas Pirot for Soliparty, 2025

Sources

[1] Motivation+Aktion, Michael Schmitz, abgerufen: https://studiomichaelschmitz.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Motivation-und-Information_StudioMichaelSchmitz_LQ.pdf, 23.11.2025, 14:10.

[2] Screenshot: https://studiomichaelschmitz.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Motivation-und-Information_StudioMichaelSchmitz_LQ.pdf, 23.11.2025, 13:34.

[3] own photography

[4] Forensic Architecture Logo, abgerufen: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Forensic_Architecture_Logo.png, 24.11.25, 12:49.

[5] Correctiv Jahresbericht 2024, abgerufen: https://correctiv.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/CORRECTIV-Jahresbericht-2024-Web.pdf, 03.01.2026, 14:25.

[6] Logo Abgeordnetenwatch, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2025_Abgeordnetenwatch_logo_ohne_Claim.svg, 04.01.2026, 14:30.

[7] own photography

[8] own photography

[9] https://www.instagram.com/p/DMdXcm9MmfW/?img_index=9, 03.01.2026, 15:07.

Related Projects

Nächstes Jahr In… (2022)

Anthology and exhibition on Jewish life in Germany, visualized in comics. → See project

Motivation+Aktion (2017)

Communication design project encouraging civic engagement and participation. → See project